Syriac inscriptions on ancient tombstones in cemeteries in modern-day Kyrgyzstan hinted to a trading community devastated by the plague, leading to a multi-disciplinary international study.

So we all did a little complaining over the past two years of the COVID-19 outbreak. Some people felt put off by having to wear a mask all the time, others got stir crazy staying at home for so long. But if you compare the whole experience to the outbreak of the medieval Black Death plague pandemic, that might put things in perspective and we can be thankful for modern medicine.

That plague – caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and passed on by infected fleas hosted by rodents – first entered the Mediterranean in 1347 via trade ships transporting goods from the territories of the western part of the Mongol empire in the Black Sea region.

From there it spread reaching Europe in 1348, hitting the Middle East and northern Africa, wiping out almost 60 percent of the population in this large-scale break out which became known as the Black Death. This first wave further then extended into a 500-year-long pandemic, the so-called Second Plague Pandemic, which lasted until the early 19th century. No vaccines back then.

Now, by utilizing technology from the relatively new archaeological field of archaeogenetics to analyze DNA from human remains found in ancient graves in Kyrgyzstan over 140 years ago, a multidisciplinary team of international researchers suggest that this Second Plague pandemic originated in Central Asia.

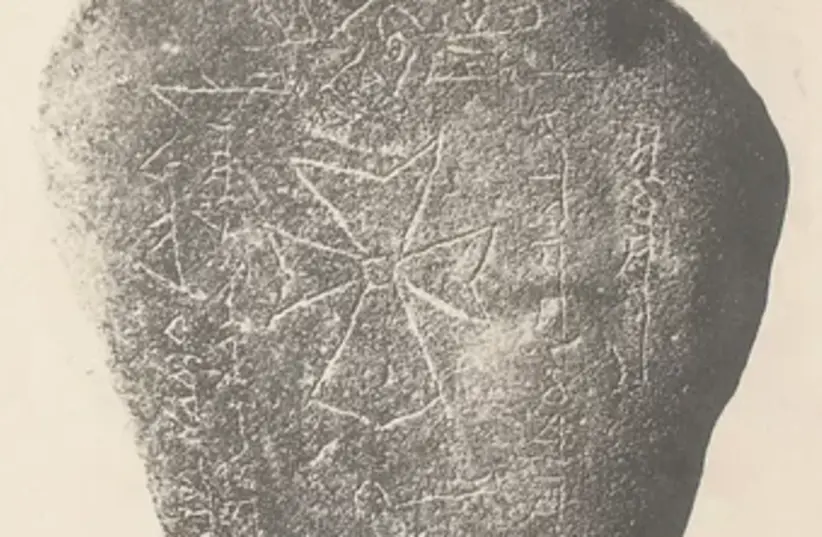

Syriac inscriptions on the numerous tombstones noting that the people had died in the years 1338-1339 of an unknown illness provided the researchers with the evidence the cause of their death may have been the plague.

A press release from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany noted that in their study the multidisciplinary international team of scientists, including researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the University of Tübingen, in Germany, and the University of Stirling, in the United Kingdom, obtained and studied ancient Yersinia pestis genomes from these ancient tombstones, which listed “pestilence” as the cause of death for the buried individuals, tracing the pandemic’s origins to Central Asia.

The team included researchers in history, archaeogenetics and anthropology.

The result of their study was published recently in the British scientific journal Nature.

The study

For some time, despite intense multidisciplinary research, the geographical source of the second plague pandemic remained unclear, with different hypotheses based on historical records and modern genomic data suggesting sources ranging from western Eurasia to eastern Asia, noted the press release. One of the most popular theories has supported its source in East Asia, specifically in China.

But, so far the only available archaeological findings providing any clues have been the tombstones, located near Lake Issyk Kul, in what is now Kyrgyzstan.

The researchers noted in their paper that the available tombstone inscriptions, burial artifacts and coin hoards found in the graves, and historical records indicate that there had been diverse communities relying on trade and maintaining connections with several regions across Eurasia in the Chüy Valley where the tombstones were found.

“Such links may have contributed to the spread of infectious diseases to and from this region during the fourteenth century,” they wrote.

“Such links may have contributed to the spread of infectious diseases to and from this region during the fourteenth century.”

The study’s authors

In recent years, comparisons between ancient and modern Yersinia pestis genomes have shown the Black Death to be associated with a “star-like emergence” of four major lineages, they added.

The researchers studied DNA data from seven individuals from two cemeteries. They said in their report that by combining archaeological, historical and ancient genomic data they were able to show a “clear involvement of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis in this epidemic event.”

“We could finally show that the epidemic mentioned on the tombstones was indeed caused by plague,” said Phil Slavin, one of the senior authors of the study and an economic and environmental historian at the University of Stirling, UK, in the press release.

Until now, the exact date of the “Big Bang” diversification event which researchers have believed was the massive source of the outbreak of different plague strains could not be precisely estimated, noted that press release. The team was able to piece together a complete ancient plague genome from the sites in Kyrgyzstan and investigate how they might relate with this Big Bang event.

“We found that the ancient strains from Kyrgyzstan are positioned exactly at the node of this massive diversification event. In other words, we found the Black Death’s source strain and we even know its exact date [meaning the year 1338,]” said Maria Spyrou, lead author and researcher at the University of Tübingen, in the press release.

Johannes Krause, senior author of the study and director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology explained in the press release that the team found that modern strains most closely related to the ancient strain are today found in plague reservoirs areas around the Tian Shan Mountains in Central Asia, very close to where the ancient strain was found. This points to an origin of Black Death’s ancestor in Central Asia, he maintains.

“It is like finding the place where all the strains come together, like with coronavirus where we have Alpha, Delta, Omicron all coming from this strain in Wuhan,” Krause told Nature News.

Tian Shan makes sense as an epicenter for the Black Death, Slavin told Nature News, since the region is on the ancient Silk Road trade route.

“We can hypothesize that trade, both long distance and regional, must have played an important role in spreading the pathogen westward,” Slavin said.