“We’ve known for a long time that the communication between different brain cells can change very dramatically … but we haven’t been able to see what happens in the whole brain until now.”

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine published a study earlier this month in Nature Communications examining in detail the brain’s process of circuit reorganization after a traumatic injury.

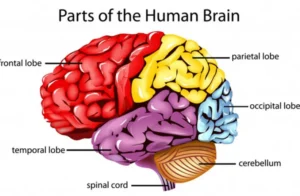

Specifically, researchers examined the global neuron rewiring that occurs after a localized injury. They focused on the large population of interneurons in the cerebral cortex that expresses the neuropeptide somatostatin and plays an important role in the process of learning and memory storage. These interneurons are also particularly susceptible to cell death upon injury.

The study

The peer-reviewed study examined experiments conducted on mice. An injury was produced in the hilus region of the hippocampus and its progress was tracked using a process called iDISCO, which uses solvents to make biological samples transparent thus making the entire brain much easier to illuminate and observe.

“We’ve known for a long time that the communication between different brain cells can change very dramatically after an injury,” said Robert Hunt, PhD, associate professor of anatomy and neurobiology and director of the Epilepsy Research Center at UCI School of Medicine whose lab conducted the study, “But, we haven’t been able to see what happens in the whole brain until now.”

The team also explored the prefrontal cortex, a region that works together with the hippocampus. In all cases, they found that neurons at the injury site gain connections from neighboring nerve cells after injury, but become disconnected from the rest of the brain.

“Understanding the kinds of plasticity that exists after an injury will help us rebuild the injured brain with a very high degree of precision.”

Prof. Robert Hunt

“It looks like the entire brain is being carefully rewired to accommodate for the damage, regardless of whether there was [a] direct injury to the region or not,” explained Alexa Tierno, a graduate student and co-first author of the study. “But different parts of the brain probably aren’t working together quite as well as they did before the injury.”

Potential brain injury treatment

Interestingly, the long pathways for connection were still present in the injured brains, but they no longer connected with damaged neurons. So, researchers set about finding out if they could repair the connections and allow damaged neurons to reconnect with more distant regions of the brain. Their methods were based on an earlier study examining neuron transplantation.

The transplanted neurons received adequate connections, indicating that it may be possible to coax the brain into repairing lost connections on its own. However, more research into interneuron transplantation is required before any attempts are made at human brain repair.

“This work takes us one step closer to a future cell-based therapy for people,” Hunt said, “Understanding the kinds of plasticity that exist after an injury will help us rebuild the injured brain with a very high degree of precision. However, it is very important that we proceed step-wise toward this goal, and that takes time.”