Foreign affairs expert Walter Russell Mead seeks to quash the ‘Israel lobby’ conspiracy theory and bust myths about US-Israel ties in his new book.

Israel has been an object of fascination for Americans since long before the establishment of the state, with the founders repeatedly comparing the fledgling republic to ancient Israel. And Israel was on Team America for almost all of its existence – even when it felt a chill from Washington.

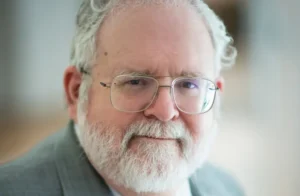

Walter Russell Mead, Wall Street Journal columnist and foreign affairs professor at Bard College, sets out to examine that relationship in his new book Arc of a Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People, reaching some surprising conclusions. He debunks myths about the American Left and Right’s roles in supporting Israel and argues that Christians in the US played a more instrumental role in drumming up support for Zionism than American Jews did. He also thoroughly demolishes the myth of an all-powerful “Israel lobby” guiding US foreign policy and discusses how the American tolerance has not allowed antisemitism to fester, while warning that contemporary culture wars are corroding that tradition.

Mead spoke with The Jerusalem Post about his new book and the current US-Israel relationship. The interview has been edited and condensed.

You write that Americans exaggerate their influence on the region, that posits that the influence of non-Jewish Israel supporters was greater than people think. How do those things come together?

I think probably the most important decision the US ever made regarding the future of Israel was the decision to cut mass emigration from Europe by 90% in 1924. As I say in the book, I think if we look at what percentage of Jews leaving Europe went to Palestine, and what percent went to the US before 1924, something like 2 to 3% went to Palestine and 80% went to the US, more if you include Canada and so on. It’s very interesting to speculate: If the US had kept open mass immigration, would there have ever been a large enough mass of Jews in Palestine to actually create a state?… The American Jewish community was unanimously opposed to that decision, for the obvious reason they wanted their friends and relatives to still be able to come to America and because they thought it was kind of unjust…

I think from an American point of view, our conscience will always bear the memory, that if we had a different immigration policy in the 1920s and ’30s, there might never have been a Holocaust. The war would have been a smaller disaster. But on the other hand, would there be a State of Israel if Jews had been free to go elsewhere?

Is that question one of the things that inspired you to write this book?

Hypotheticals are intellectually interesting, but American policy was what it was, and Israel is here…

Several things inspired me to write the book. One was my sense that people in the US and around the world project anti-Semitic tropes and legends onto their discussion of US-Israel policy. I’ve traveled all over giving lectures and meeting with people for the State Department as a speaker, and it was almost a universal conviction, not just in the Middle East, but I found it in Europe and Latin America, Malaysia, that the Jews run America, which is why America has a pro-Israel policy.

Now there’s a debate, is it that the Jews in Israel tell the American Jews what to do? And then they pass the instructions on to the American government? Or is it that the Jews in America are actually using Israel as part of their even grander Jewish plot? That kind of hate is morally reprehensible, but also, that kind of ignorance is dangerous.

Part of the book is just trying to clear some things I want to dispel some rancid urban legends about Jews and Jewish influence.

What’s a little-known fact or misunderstanding that you think Israelis need to better know about the relationship with the US?

I spent a lot of time in the book, looking at the politics in the US, under [president] Harry Truman, between 1945 and 1948, leading up to the War of Independence. And it seems very clear to me that the idea was very common in America… that somehow Harry Truman saved the Jews. There’s the story that in the spring of 1948, it all looks very dark and Harry Truman is refusing to see any Zionists, any American Jews. But then little Eddie Jacobson, Harry Truman’s old Jewish friend and business partner from Missouri comes in and says – kind of like Queen Esther – says to the moody gentile ruler, you’ve got to do something for my people. And so, Truman meets with [Chaim] Weizmann and then everything is settled, Israel was saved, and even the littlest Jew in the littlest town in America can play a role. That’s this beautiful legend that people have. It’s factual in the sense that Jacobson did intervene, and Truman did have a meeting with Weizmann.

But in fact, American policy did not change as a result of that meeting, and right up through [the Israeli] Declaration of Independence, the US opposed the declaration of a Jewish state and wanted a new trusteeship to replace the British. The last thing the Israeli cabinet did before voting for independence was to vote to reject the American proposal for longer mediation. Israel actually begins its independent career by saying no to the US.

Truman pushed through recognition of the new State of Israel, despite State Department opposition.

What Truman said to the State Department in May ’48 is, “you didn’t give me a policy. You told me the Partition Plan was terrible. I said, fine, what should we do? You said a new trusteeship to avoid a war and then we’ll have time to figure it out. Nobody supported the trusteeship and the old mandate ends at midnight. What should I do? You have no answer. Meanwhile the Soviet Union is going to recognize Israel.”

“You didn’t give me a policy. You told me the Partition Plan was terrible. I said, fine, what should we do? You said a new trusteeship to avoid a war and then we’ll have time to figure it out. Nobody supported the trusteeship and the old mandate ends at midnight. What should I do? You have no answer. Meanwhile the Soviet Union is going to recognize Israel.”

Harry Truman

That was not a good position for him to be in. There may be a connection between Weizmann’s visit and Truman’s thinking at this point, but there’s no documentation…

Truman didn’t save the Jews in 1948. The Jews saved Truman because the success of Israel made Truman’s policy look terrific.

That brings us to what you say in your book, that the US-Israel relationship didn’t grow because Israel was weak, but that once Israel was strong, the US was more interested in Israel.

That is true in all international relationships, not just the US-Israel relationship. That is one of the points I want to make. If you really study the US-Israel relationship, it doesn’t look that different from other relationships. The same questions and interests go into the thinking on both sides.

The hypothesis that the Jews or the Israel lobby are making the US behave differently where Israel is concerned just doesn’t fit the facts as far as I can tell.

One of the things that you wrote is that you thought Americans are overly optimistic about the prospects for peace. The Biden administration has said there’s not going to be peace with the Palestinians in the short term, so they’re trying to push for small incremental changes. How do you evaluate that policy?

It’s a bit too soon to tell… but I think that there is a growing sense everywhere that the two-state solution has less support among Palestinians and Israelis.

I do think the Biden administration understands that there are limits to what it can achieve and, in this way, I would say it shows a good deal more intelligence than the Obama administration did.

A big part of President Joe Biden’s upcoming visit to the region is a stop in Saudi Arabia, which is interesting in and of itself, but there is also a growing relationship between Israel and Saudi Arabia. How much of that do you think is coming from the Biden administration as opposed to a continuation of what was happening anyway?

I don’t think that either Israel or Saudi Arabia need help from the US if the two of them want to reach an agreement. If we go back a long time in the history of peace negotiations, Americans tend to exaggerate their role in all of this. The key decisions in any peace negotiation ultimately have to be taken in the Middle East and Americans just don’t have that much influence. If Americans tell the Saudis to give women equal rights, the Saudis don’t do anything about it. If the Americans tell [President Abdel Fatah al-] Sisi in Egypt, let’s have more democratic rights, he does nothing about it. If the Americans say to the Israelis, can’t you stop building settlements as a general rule, the Israelis don’t do anything about it. I think there’s a kind of narcissism in America that is sometimes reflected in the rest of the world press that exaggerates our influence over all these things.

It’s clear that Israel and the Saudis now have, you know, in some ways a history of clandestine cooperation that stretches back to their common efforts against [Egyptian president Gamal Abdel] Nasser in Yemen back in the 1960s. This is not some surprising deal that just does come out of nowhere.

It’s primarily driven by two things. One is a joint fear of Iran and the other is a joint lack of confidence in the US. Those two things have made both governments more aware of how important they are to each other and more willing to work more closely together.

The US is negotiating a return to the 2015 Iran deal, which both Israel and the Saudis don’t like to varying degrees. At the same time, the US is helping form this Middle East air defense alliance against Iran. Is that helping countries that oppose the Iran deal to trust the US more or less than they did a decade ago?

I would say that they’re more willing to work with each other because they think they need to, given the unreliability of the US, and because of their fear that, as the US steps back, Iran is growing in power. They both want America back in the region as much as possible, so any proposal from the Americans is likely to have people interested in it and look for ways to say yes even if they secretly mean no. That’s what diplomacy does…

The advantage in some ways to the Biden administration of renewing relations with the Saudis, and working with Israel more directly, is that, in turn, may make Iran think they really are serious about Plan B [if there is no Iran deal], and maybe this is the moment where they had better just sign on the dotted line. From the Biden point of view, doing this advances both of their policies.

There is a lot of concern about Israel losing popularity in the US. How worried do you think Israel needs to be and what do you think is at the root of this decline?

Let me start by saying I don’t actually think Israel’s security or survival depends on its popularity in the US. In 1948, the US might have recognized Israel, but Truman almost immediately started pressing for territorial concessions, and in the ’50s, the Eisenhower administration tried to get Israel to give up the Negev and take a lot of refugees, and Israel was an incredibly weak state. It had a terrible economy, was overwhelmed with refugees and facing enemies who in many cases were better equipped than they were. And Israel still stuck to its knitting, and got the job done.

I say in the book that Israel didn’t become strong because it had an American alliance, it got the American alliance because it became strong. So, in that sense, Israel should not get into some kind of nervous emotional meltdown every time people look at a poll result from the US.

That said, the relationship offers a lot of benefits to Israel and is not something that one would lightly throw away, especially without an obvious alternative.

I do think there’s a sense in which a lot of people in Israel would like to isolate the Palestinian question completely from the relationship with the US. That’s really not realistic. Israel really does need to think these things through… It’s a puzzle, and all countries have these puzzles and things you might want to do. How do you balance them? That’s part of what politics is about, right?