The residents’ protest, which I think is very justified, has brought to the spotlight not just one component of the chronic disease of the health system.

Emergency medical professionals from throughout the country, who specialize in treating some of the most critically ill and injured patients will meet for a week of academic and organizational activity on the 30th of this month.

By the end of the event, the finals of the national competition in resuscitation will be held. The emergency medical system also needs resuscitation, and we must all mobilize to restore health justice to the country’s population.

I will analyze the situation of the Emergency Departments (EDs) according to the stages of performing basic resuscitation as an example within the story of an evening shift by a senior doctor:

A. You need to identify early on that the patient is not responding or breathing and whether the environment is safe for the caregivers

Have you not yet noticed and diagnosed that the medical system is in a critical condition of an ongoing illness?

I enter the ED for an evening shift. I find a busy ward and in the waiting room, 30 people who have not yet been examined. The ward has a total of 45 beds, all occupied.

In the resuscitation room (the area designated for the sickest or most severely injured) two beds out of a total of four are occupied by patients in critical condition waiting to be transferred, one to the operating room and the other to the intensive care unit. I make sure they get proper care, and their condition stabilizes.

I ask that I be notified immediately of any change in their condition. I am moving to the area in the ED designated for acutely ill patients.

I scanned the room, looking for the “golden patient,” the one whose condition may worsen in the next hour and has not yet been diagnosed and treated. While scanning, more patients keep coming in.

The ED has become the “default” of the medical system. Family physicians not only have a fixed time for each patient, but they are also restricted in their ability to refer for advanced testing. The system in the community is saturated with the unavailability of appointments for advanced imaging, specialist doctors, or elective surgeries.

I meet an elderly patient who was sent to the hospital by the family doctor to undergo a CT scan because he was unable to perform it at a reasonable time in the community.

Next to him lies someone who has severe back pain but could not be seen by a spine specialist for a month. Another patient, a resident of a nursing home where there is no doctor on weekends, was sent to us for urinary retention. I quickly handle the many visits; however, I do not have time to give long and patient explanations to family members.

Given the situation, already at the beginning of the shift, I feel frustrated. Just then the turning point occurred. A nurse draws my attention to a 28-year-old girl who “does not look good” and has been waiting for two hours with abdominal pain in the last available bed.

B. You should call for help and lay the patient on their back

I reach for her and find her as pale as a ghost. I immediately recruit the team and move her to one of the available beds in the resuscitation room. She is connected to a monitor and in the process, the intern inserts an intravenous line and takes blood.

The patient’s husband says that she has been suffering from lower abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for two days. He says that his wife does not suffer from any known medical problems and that she does not take medications. She has no allergies and has not had any surgeries.

Her blood pressure is low she had a rapid heart rate. I ask that the laboratory perform blood work including a pregnancy test. I also request a sample of her blood type and order two units of blood. The husband shouts that his wife is not pregnant and that all the tests are not necessary. I insist on checking the blood and urine for possible pregnancy. I request that they bring me an ultrasound machine.

C. You need to start compressions in the center of the chest fast and strong (it’s time to act)

Measurement of the vital signs shows low blood pressure, rapid breathing, a temperature of 36 degrees Celsius, and normal oxygen saturation. I complete the physical examination according to the principles of the ABCs and examine her systematically from head to toe.

I find a bloated and very tender stomach. I perform a bedside ultrasound that reveals free fluid in the abdominal cavity. I ask myself; how did this poor young woman wait two hours without anyone recognizing the severity of her condition.

Immediately I remember that in the morning shift there were only 2 senior doctors in the whole ED and that one nurse worked 12 beds at a time (in my training in Australia I got used to having one nurse for every 4-5 patients).

D. You must give the appropriate patient an electric shock as early as possible and remember that resuscitation is not just an electric shock!

I continue to provide intravenous fluids and ask them to heat the units of blood that are in the refrigerator in the resuscitation room. I understand that at any moment the young patient may go into cardiac arrest, and I may have to perform more extreme procedures.

E. You must diagnose and treat the disease that caused the patient to reach the resuscitation stage

The nurse comes back to me in a panic and reports that in the blood and urine test (in the resuscitation room in the hospital there is a device for point-of-care testing) the patient has an increase in lactic acid in the blood (a danger sign), her hemoglobin is 7 g / dL (extreme anemia – normal value 12 g / dL) and the urine test is positive for pregnancy.

An ultrasound examination focused on the uterus does not reveal a pregnancy sac and from this I conclude that the young patient has an ectopic pregnancy that has ruptured and is causing massive life-threatening bleeding.

I immediately ask that they call the operating room of the gynecology department and the senior gynecologist (yes, in gynecology there is a senior doctor and specialist all night to make critical decisions in real time, contrary to what happens in the country in most EDs).

We meet the senior gynecologist at the entrance to the operating room. The patient enters emergency surgery while we are injecting the last milliliters of blood left in the bag into her veins.

F. Once resuscitation is complete you must treat the staff

I meet the patient’s husband outside the operating room and explain to him about his wife’s condition and the life-saving surgical intervention she is undergoing.

I return with my team to the ED (it is packed with patients because I have not been present for the last 40 minutes). We sit down for a debriefing to discuss the actions we performed- what went well and what needs improvement. I try to encourage my shift staff.

A long shift is ahead of us while our resources are extremely limited. The staff must now address the problems of other patients. I turn to look for the next “golden patient” inside a hospital laden with frustrated patients and families and an exhausted staff.

Analysis of the situation

If you are lucky and do not need to visit one of the country’s EDs, you are not aware of the long waiting times. The average waiting time for a person in the ED is 4 hours. A queue of stretchers with MDA staff waiting for a bed is a common sight. The nursing staff has difficulty reaching out to the many patients under their care (one nurse caring for 12 patients on a good day).

The waiting time for patients to move to inpatient wards in some hospitals is longer than a day because the wards are not available to receive them. (A condition that requires the medical and nursing staff of the already saturated ED to give them treatment as if the patient were hospitalized).

Internal system crash

The healthcare system and its various branches does not plan for the future needs of the citizens of Israel.

There is no synchronization between the development of the services and the rate of increase in referrals and the aging of the population.

There is a paucity of inpatient wards, lack of geriatric rehabilitation, lack of operating rooms, and scarcity of beds in recovery and intensive care units.

Due to the lack of all these resources the patients stay in the hospital for longer periods of time where they are exposed to many infectious diseases and receive suboptimal treatment in a busy ward by an exhausted staff.

Everyday, dozens of family members ask the same question to the exhausted:

“When will my mom go up to the ward?”

Does anyone in the hospital administration, the Ministry of Health, or the Ministry of Finance have an answer to this question?

External system crash

There is a shortage of doctors in the State of Israel. One of the following facts that cannot be disputed is the low number of medical graduates who begin specialization in internal medicine and core professions. In addition, there is an abandonment of doctors to other professions that are not necessarily related to medicine, or alternatively to other countries in the hope of a better future for them and their family. A similar thing is happening to the nursing profession.

There are fewer family physicians and those who are already working, operate under a HMO compensation system that forces them to see a patient every 10 minutes in order to make a living.

As a result, EDs are flooded with numerous referrals from family physicians who do not have the time or resources to care for patients who in other countries would receive care in the community.

Family physicians refer patients who cannot receive specialist advice or imaging at reasonable times, or those whose wait time is too long.

Every patient who cannot undergo non-urgent intervention within a reasonable time by the community setting comes to the hospital and dozens of patients daily lie for long hours in beds that were meant for emergency cases.

The Collapsing Emergency Department

The ED has become the default of the medical system, but the “almighty” department also has limitations. There are no standards, the shifts are long, and there must be 24/7 staffing.

Factually, the medical staffs of the ED are among those suffering from the highest incidence of medical PTSD. We call this condition BURNOUT. The staff member inevitably becomes an indifferent and hardened person, losing interest in the profession and a zest for life.

This is the main reason that after many years of studying and passing exams, the departments lose professionals, in whom an immense amount of resources have been invested in order to train them.

Worldwide this phenomenon has led to the development of strategies to minimize the burnout of emergency medical teams. In most Western countries the position of specialist in emergency medicine is 3 clinical shifts a week (in contact with patients- including nights and weekends) of 12 hours each.

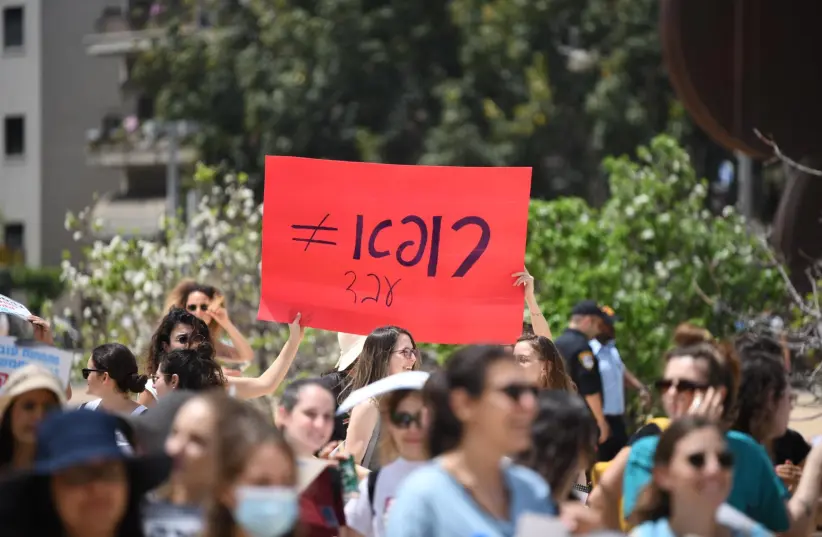

The residents’ protest, which I think is very justified, has brought to the spotlight not just one component of the chronic disease of the health system.

Lack of planning, lack of creative thinking, lack of initiative, and lack of leadership.

What can be done?

We suggest:

A Move of 3 years to train and recruit personnel. We need to open 300 job lines for specialists in emergency medicine and 250 job lines for resident trainees when the distribution of spots will be based on the number of visits to the ED (without necessarily preference for the center of the country).

Switch to a work week of 3 shifts of 12 hours.

Compensate so that the monthly salary is commensurate with the effort of the profession (6 years of medical school, one year of internship and additional years of residency training) including a reward intended for advanced training and mentoring of interns and students.

Ensure equality between the medicine in the center of the country and the periphery.

Ensure a safe work environment for all medical staff with zero tolerance for physical or verbal violence.

What are we specialist doctors doing?

We are committed to continuing to teach and instill in the future generation the love of the profession, concern for the patient, and scientific curiosity.

This is the main reason we are organizing this year “National Emergency Medicine Week,” an event in which there will be lectures with experts from Israel and abroad, a national simulated resuscitation competition, a day of workshops, leadership meetings, and a national scientific conference at the Tel Aviv Expo.

We will not give in to the existing difficulties and will continue to fight for a better answer to the question of the worried son:

“When will my mother go up to the ward?”

The author is the Chairman of the 25th Scientific Conference of the Israeli Association of Emergency Medicine and a specialist in Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine.